Spring is spinning, but it is not too early to be thinking about poinsettias. They are coming up soon enough. Previous Production Pointers have focused on both establishing and finishing containerized poinsettias. This month, we focus on propagation.

First, start with a clean facility. Take the time after spring, before cuttings arrive, to clean the areas where cuttings will be propagated — from Stage 1 (sticking) through Stage 4 (toning). While this is important for every crop, eliminating the potential for soft rot (Erwinia) starts here. But it isn’t just diseases we are preparing for — we want to minimize insect pests, too. A clean greenhouse goes a long way, but before cuttings are stuck, they can be completely, but quickly, submersed in low concentrations of horticultural oils or insecticidal soap.

When poinsettia cuttings arrive, prepare space in a cooler for them. This can help serve a few purposes. First, it can help to cool cuttings and reduce the plant temperature — and it can also help rehydrate them. Second, it can buy you a little time to make sure you have everything ready in the headhouse or a shaded place in the greenhouse to stick cuttings. When getting cooler space sorted out, be sure it is going to be at the right temperature for poinsettias. Air temperatures in coolers should be between 50 to 55°F to sufficiently cool them while avoiding damaging cold-sensitive poinsettia.

In addition to preparing cooler space for cuttings, you’ll also want to prepare your substrate for propagation early, too. Stabilized substrates such as phenolic foam or physically bound loose substrates are excellent choices for poinsettia propagation. Plus, stabilized substrates allow for cuttings to be transplanted earlier than loose-filled substrates. And if loose-filled substrate is being used to pre-fill propagation trays, be sure not to stack trays on top of each other. Whether the pH of soilless peat-based mixes is adjusted with limestone, or phenolic foam adjusted with fertilizer solution, use a target of 5.8 to 6.2 for poinsettia.

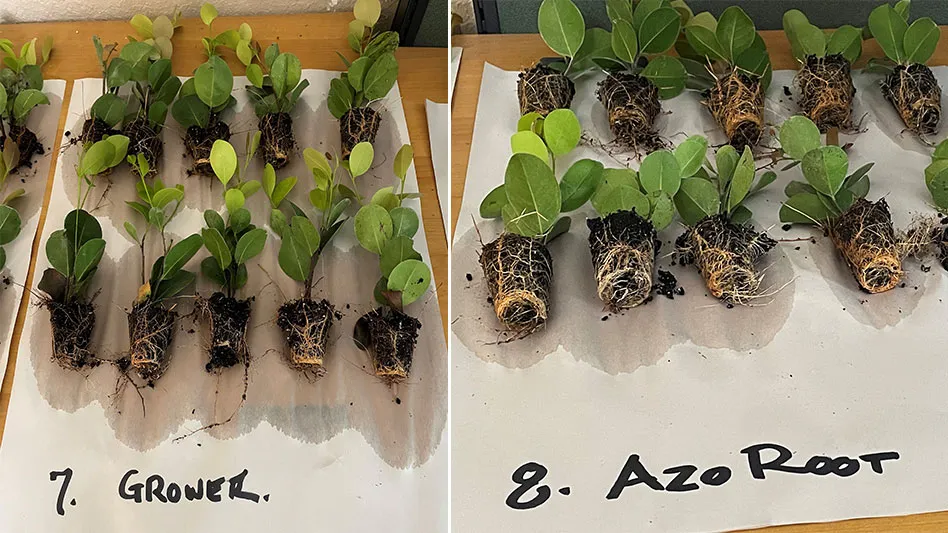

Rooting hormones should be used to improve rooting in poinsettia, hastening root growth and improving uniformity across crops. The most common rooting hormone is indole-butyric acid (IBA), though some formulas will also include naphthalene-acetic acid (NAA). Hormones have traditionally been suspended in a talcum powder or water solution, and the basal end of cuttings were dipped prior to sticking them. While this is certainly still an effective means of applying rooting hormone to poinsettia cuttings, newer auxin formulations are available to apply as a foliar spray after cuttings are stuck. Compared to dipping cuttings, spraying reduces the labor required to stick poinsettia cuttings by eliminating a step.

Use high-quality water for misting poinsettia cuttings. The frequency of mist during the summer — and resulting volume of water applied to cuttings — is not insignificant. To improve the efficiency of misting and enhance hydration, non-ionic surfactants — also called spreader-stickers or spray adjuvants — can be used to reduce the surface tension of water on the leaves, breaking water beads and droplets and improving coverage on foliage. Misting frequency and duration interact with the growing environment and stage of cutting development. Keeping facilities shaded will reduce air and plant temperatures and reduce mist requirements. As cuttings proceed from Stage 2 (callusing) into Stage 3 (root development), the frequency of misting will decrease. Close monitoring of root development will help manage mist strategies and help avoid excessive moisture, leading to soft rot (Erwinina).

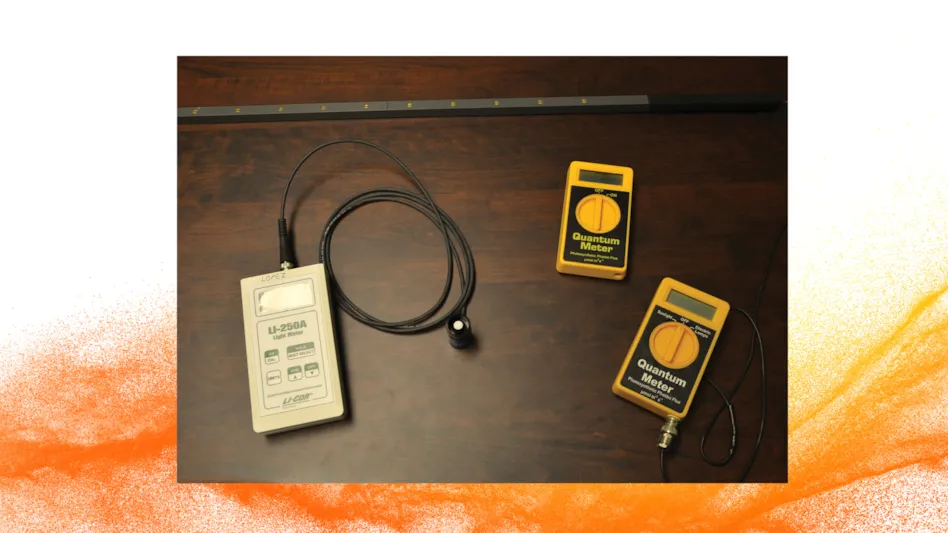

One of the most important factors when propagating poinsettias is managing light intensity. Poinsettia cuttings are sensitive to excessive light, and it is ideal to keep the intensity between 150 and 250 µmol·m–2·s–1, a target daily light integral (DLI) of 4 to 5 mol·m–2·d–1. Light intensities higher than this can damage foliage. Shading will be needed, and there are a variety of options. Shading is essential to diminish the summer sun’s intensity and can range from more season-long options such as whitewash or black saran to retractable aluminized shade cloth. As cutting progresses through root development and toning, light intensity can be increased incrementally to acclimate cuttings to light intensities and DLI approximately twice what they were in callusing. This can be achieved by changing shading programs to increase light intensity (for retractable shade) or moving cuttings to areas with less or no shade (for permanent shade).

Warm temperatures can improve callusing and root initiation for poinsettia cuttings. Keep temperatures below 82°F, if possible. But the summer can be too hot. As mentioned earlier, shade is useful in reducing excessive heat, as well as light. Excessive heat can stress cuttings or, worse, promote soft rot. Throughout propagation, as cutting progresses through Stage 3 and Stage 4 (toning), air and substrate temperatures can be reduced to the mid-70s — if outdoor temperature will allow it.

Fertilizing during propagation is a great way to avoid nutrient deficiencies and produce healthy liners for transplanting. Low concentrations (50 to 75 ppm nitrogen) of water-soluble fertilizer can be used, applied in mist or other means of overhead irrigation. Poinsettia leaves are sensitive to phosphorous and can be damaged, and growth can become hardened. A light rinse with clear water to get fertilizer off foliage — without leaching substrate of nutrients — can help avoid foliar damage.

There is not much to compete with poinsettia cuttings in the greenhouse in the summer, and there are opportunities to be had with your space. Take that time to focus on the best management practices you can provide poinsettia cuttings and start your crop with the best rooted liners possible.

Explore the May 2024 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find you next story to read.

Latest from Greenhouse Management

- Landmark Plastic celebrates 40 years

- CropLife applauds introduction of Miscellaneous Tariff Bill

- Greenhouse 101 starts June 3

- Proven Winners introduces more than 100 new varieties for 2025

- UF/IFAS researchers work to make beer hops a Florida crop

- CIOPORA appoints Micaela Filippo as vice secretary-general

- Passion grows progress

- Registration opens for Darwin Perennials Day