Light affects plant growth in several different ways. In addition to promoting photosynthesis and growth (light intensity) or controlling flowering and dormancy (daylength), the light spectrum or quality can serve as a signal to influence growth and development of greenhouse crops.

Although different colors or spectra of light serve as signals for different aspects of plant growth and development, red and far-red light and the red-to-far-red ratio (R:FR) play important roles for many greenhouse crops.

Understanding red and far-red

Understanding how red and far-red light act as a signal for plants can subsequently help you understand how it is managed.

Phytochrome is a photoreceptor that senses red and far-red light. It is photo-reversible pigment, meaning that it changes forms depending on the light it senses. Phytochrome red (Pr) senses red light with a peak around 630 nm and, after sensing the red light, changes into phytochrome far-red (Pfr). When Pfr senses red light at a peak around 760 nm, it converts to Pr. There is never a time when all phytochrome is entirely Pr or Pfr; rather, the two forms simultaneously exist, and their relative proportion to one another — the phytochrome photoequilibrium (PPE) — acts as a signal to influence plant responses to light quality.

One of the most important plant physiological effects of red and far-red light on plants is their effect on stem elongation. When plants are growing in conditions with a higher proportion of far-red light, it promotes stem or internode elongation characterized as the “shade avoidance response.” The phrase “shade avoidance response” comes from the fact that when plants are growing in shade created from other plants, this environment is rich in far-red light, since leaves preferentially absorb red light for photosynthesis.

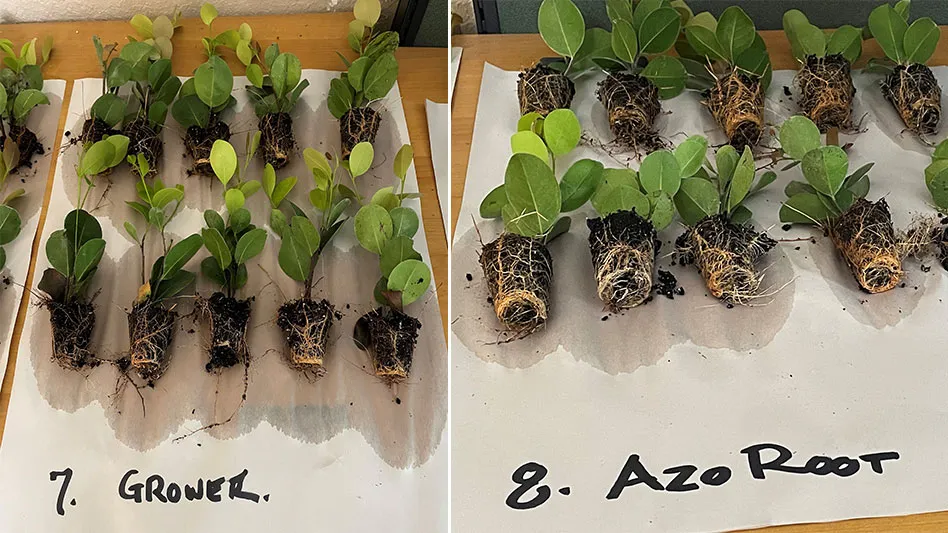

In production greenhouses, there are ways environments rich in far-red light can be created. The first and most common can be when plants are grown at high densities or with close spacings. Think about the vase-like appearance of mums or the stretched stems of poinsettias when they're grown close together, compared to the more rounded and compact forms when plants are grown at lower plant densities and with more space between plants.

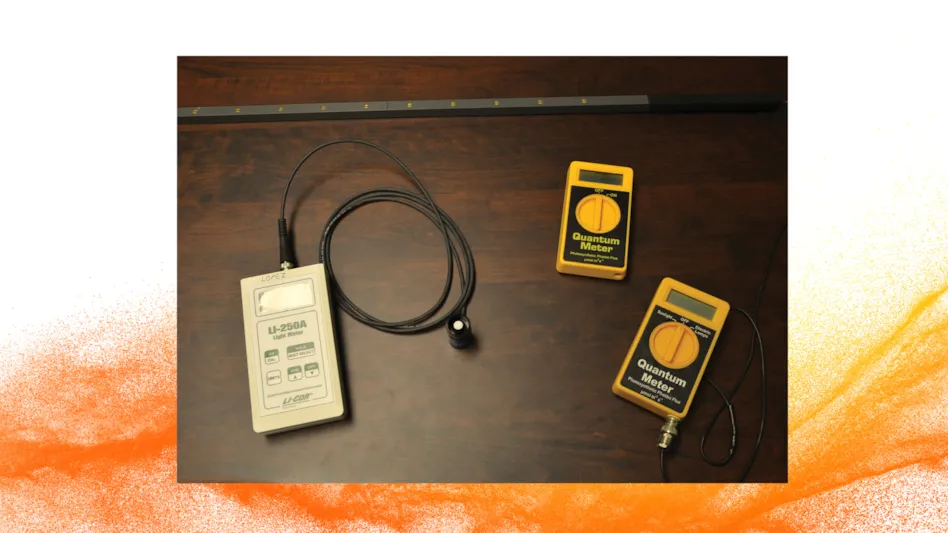

In addition to spacing affecting the R:FR ratio, hanging baskets suspended above crops similarly affect the light quality below them; the foliage of plants in hanging baskets will preferentially absorb red light and lower the R:FR ratio for plants on benches or floors below them, and this effect increases as the number of hanging baskets increases. Lights used for supplemental or photosynthetic lighting, such as high-pressure sodium (HPS) lamps and high-intensity light-emitting diodes (LEDs), are usually rich in red light, which can help compensate for lower R:FR ratios created by close spacings or hanging baskets.

Flowering for many ornamental greenhouse crops is controlled by daylength, with short- and long-day plants flowering in response to short days (or long nights) and long days (or short nights), respectively. Under naturally short days, photoperiodic lighting such as day-extension or night-interruption is used to extend the daylength or interrupt the night, respectively, to promote flowering of long-day plants, or to inhibit flowering of short-day plants.

The R:FR ratio effective for extending the day or interrupting the night is different between these different types of photoperiodic response groups.

For short-day plants, red light is essential for plants to perceive “day” and far-red light alone is not effective. Alternatively, long-day plants require a sufficient amount of far-red in addition to red light to perceive “day,” and red light alone is not effective. Although responses vary among photoperiodic response groups, this doesn’t mean you need separate lights for managing photoperiod for short- and long-day plants.

Traditionally, incandescent light bulbs have been used for both short- and long-day plants, as their R:FR was effective for both crops. When compact fluorescent lamps began to be used for day-extension and night interruption, they were effective for short-day plants but were less effective for some long-day plants because of the low levels of far-red light; using both incandescent and compact fluorescent lights together improves the R:FR ratio for long-day plants and alleviated this delay. The introduction of LED “flowering lamps” — different from the lights developed for supplemental lighting — has provided producers with a selection of different lights with varying R:FR ratios, as well as a long luminous lifespan and energy efficiency.

Efficient seedling plug production requires fast and uniform germination. In addition to having specific temperature and moisture requirements, some seed-propagated species require light for germination. Specifically, red light can promote germination of these species, while far-red can inhibit it.

The evolutionary adaptation to this R:FR light as a signal is very similar to the shade avoidance; more red light or a higher R:FR light ratio would indicate a seed is not being shaded out and upon germination would receive ample sunlight to grow, whereas more far-red light or a low R:FR ratio would indicate a seed is being shaded by another plant and may not receive sufficient light to grow after germination. As with electrical light sources used for flowering control, be mindful of any lighting used to promote germination in germination chambers to be sure there is a sufficiently high R:FR ratio.

While we commonly think about light intensity and daylength for producing high-quality crops efficiently, keeping in mind the effects of red and far-red light and the R:FR ratio on crop growth and development will help avoid unwanted stretch, problems with flowering control, or delays in germination.

Explore the April 2022 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find you next story to read.

Latest from Greenhouse Management

- Landmark Plastic celebrates 40 years

- CropLife applauds introduction of Miscellaneous Tariff Bill

- Greenhouse 101 starts June 3

- Proven Winners introduces more than 100 new varieties for 2025

- UF/IFAS researchers work to make beer hops a Florida crop

- CIOPORA appoints Micaela Filippo as vice secretary-general

- Passion grows progress

- Registration opens for Darwin Perennials Day