From more toned and controlled plant growth to minimizing diseases and resource use, there are a host of benefits to growing dry. While not all plants may be considered “drought tolerant” per se, they all have an acceptable degree of “growing drier.” What is dry for a New Guinea impatiens crop will not be what is considered dry for lantana. No matter what crop we are talking about, there are opportunities to grow it drier, and I will cover some approaches to achieve this.

Substrate selection

You should prepare to grow drier before planting by designing or selecting substrate that will help you be successful. Most substrates used in containerized greenhouse crop production are generally made up of a majority (i.e. 70% to 80%, by volume) of ground sphagnum peat moss, which can be either hydrophobic or hydrophilic. When moistened and hydrated, sphagnum peat moss readily takes up water, but when it is dried out, it won’t. You have probably already experienced this when you’ve irrigated a crop that had gotten too dry, and the water runs off the substrate surface and down the inside of the container (channeling). One way to remedy this is to double water, where a crop is first watered lightly, then watered again more thoroughly anywhere from 15 to 30 minutes after the first irrigation. The first irrigation serves to rewet peat and turn it from potentially hydrophobic to hydrophilic, allowing it to fully absorb the second, more thorough irrigation.

Substrate components can also help rewetting when growing dry. Wetting agents, or non-ionic surfactants, can be added to help make rewetting easier. Additionally, some substrate components like chopped, shredded or ground coconut coir remain hydrophilic even when dried down and rewet easily.

Physiology

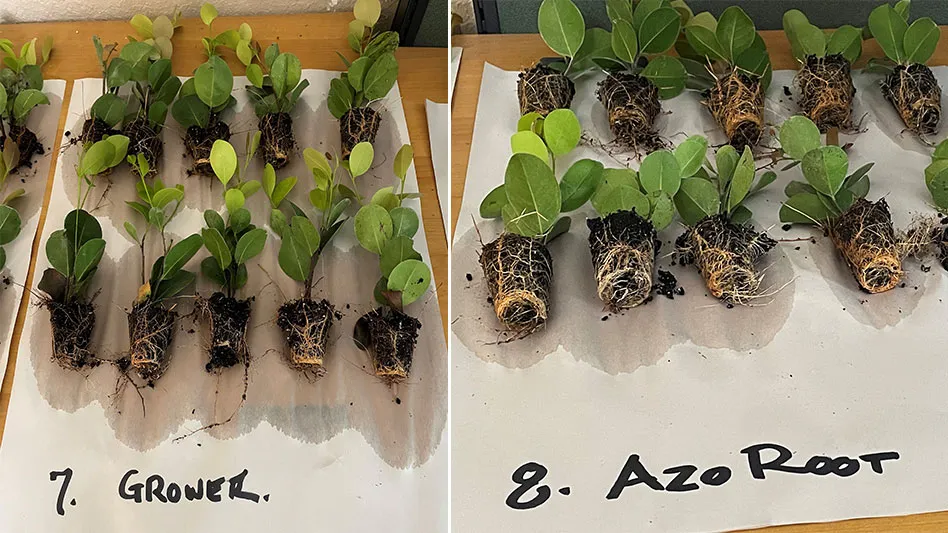

Growing dry is not just a mindset as a grower — in some ways it is for plants, too. One way plants can be grown drier is by physiologically adapting to the drier conditions. When we talk about “toning” plants, pushing their wet and dry cycles play a role. The drier conditions cause a thicker waxy cuticle to develop on foliage, and leaves don’t get quite as large. Both of these adaptations subsequently make them more adaptable to growing drier. This plasticity in plants shouldn’t only be used to tone plants for transitions (seed to finishing plugs, transplanting to flowering for finished), but condition them for drier growing, too.

Trying to turn dry on a dime from wet to dry growing won’t work well if you are starting with soft plants. Soft plants, which are prone to losing water more quickly, have thinner cuticles and larger leaves. You’ll need to transition into wet and dry cycles as the plants are toned to prepare to be grown drier.

Initiating irrigation

When growing dry, one of the biggest challenges is knowing when to step in and irrigate. But for successful dry growers, this is likely their biggest strength and skill. In growing drier, waiting too long can result in excessively stunted growth and damaged plants. Careful observation and a diligent approach make pushing plants further possible.

Most commonly, the “look and feel” method is used. Visual cues are some of the most helpful: like the substrate appearance scale, where 5 is dark with free-standing water and 1 is light tan with substrate pulling back from the edge. Looking at plant foliage to see a lighter-greenish or grayish appearance is a great way to see plants that are on the edge of dry down. While slight wilting or “flagging” is clearly a sign plants are ready for irrigation, not all plants should be dried down this hard. For example, although tomato plants can get to the point of flagging before irrigation without damage, bacopa will drop its flowers if dried down this hard.

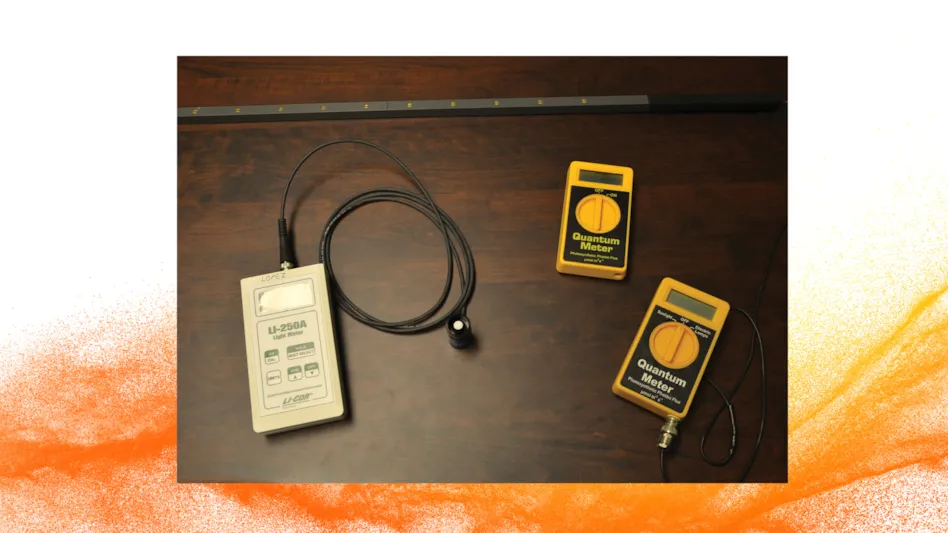

As for the “feel” part of the equation, touching the substrate to feel the moisture status or picking up containers to feel their weight gives you even more “data” to base your decision to irrigate on. Although diligently looking and feeling is a great way to grow drier, this can be subjective to different growers. Using more objective information can help a variety of different individuals find more consistent results. So instead of picking up containers to feel their weight, they can be weighed, and values can be compared to pre-determined weight thresholds used to initiate irrigation. Even more useful is the use of substrate volumetric water sensors, as these can be tied into greenhouse control systems and provide continuous, real-time measurement of moisture content in growing substrates.

It is often said that irrigation is “more art than science.” If so, then growing dry should be considered “high art.” Although it may seem like a leap of faith, take the tips outlined in this article to transition toward a drier style of growing. You may experience fewer diseases in crops; as well as use less water, fertilizer and plant growth regulator. What more could you want?

Explore the April 2024 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find you next story to read.

Latest from Greenhouse Management

- Landmark Plastic celebrates 40 years

- CropLife applauds introduction of Miscellaneous Tariff Bill

- Greenhouse 101 starts June 3

- Proven Winners introduces more than 100 new varieties for 2025

- UF/IFAS researchers work to make beer hops a Florida crop

- CIOPORA appoints Micaela Filippo as vice secretary-general

- Passion grows progress

- Registration opens for Darwin Perennials Day