The El Niño brewing in the Pacific Ocean is strong and is showing no signs of waning, according to NASA's latest satellite image from U.S./European Ocean Surface Topography (OSTM)/Jason-2 mission. Forecasters are expecting the United States to also feel the impact the warming weather pattern has already created around the world, including the possibility of drought relief in California and the U.S. West.

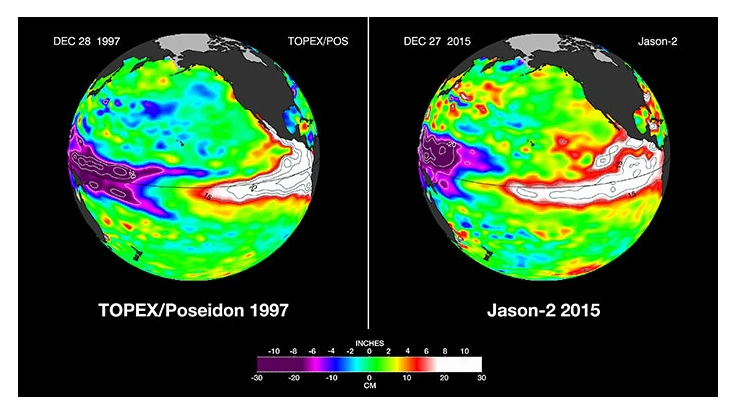

The latest Jason-2 image bears a striking resemblance to one from December 1997, by Jason-2's predecessor, the NASA/Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES) Topex/Poseidon mission, during the last large El Niño event. Both reflect the classic pattern of a fully developed El Niño.

The images show nearly identical, unusually high sea surface heights along the equator in the central and eastern Pacific: the signature of a big and powerful El Niño. Higher-than-normal sea surface heights are an indication that a thick layer of warm water is present.

El Niños are triggered when the steady, westward-blowing trade winds in the Pacific weaken or even reverse direction, triggering a dramatic warming of the upper ocean in the central and eastern tropical Pacific. Clouds and storms follow the warm water, pumping heat and moisture high into the overlying atmosphere. These changes alter jet stream paths and affect storm tracks all over the world.

This year’s El Niño has caused the warm water layer that is normally piled up around Australia and Indonesia to thin dramatically, while in the eastern tropical Pacific, the normally cool surface waters are blanketed with a thick layer of warm water. This massive redistribution of heat causes ocean temperatures to rise from the central Pacific to the Americas. It has sapped Southeast Asia’s rain in the process, reducing rainfall over Indonesia and contributing to the growth of massive wildfires that have blanketed the region in choking smoke.

In the United States, many of El Niño’s biggest impacts are expected in early 2016. Forecasters at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration favor an El Niño-induced shift in weather patterns to begin in the near future, ushering in several months of relatively cool and wet conditions across the southern United States, and relatively warm and dry conditions over the northern United States.

The latest El Niño forecast from NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center is at: http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/

In 1982-83 and 1997-98, large El Niños delivered about twice the average amount of rainfall to Southern California, along with mudslides, floods, high winds, lightning strikes and high surf. But Patzert cautioned that El Niño events are not drought busters. "Over the long haul, big El Niños are infrequent and supply only seven percent of California’s water," he said.

While scientists still do not know precisely how the current El Niño will affect the United States, the last large El Niño in 1997-98 was a wild ride for most of the nation, according to the release. The “Great Ice Storm” of January 1998 crippled northern New England and southeastern Canada, but overall, the northern tier of the United States experienced long periods of mild weather and meager snowfall. Meanwhile, across the southern United States, a steady convoy of storms slammed most of California, moved east into the Southwest, drenched Texas and — pumped up by the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico — wreaked havoc along the Gulf Coast, particularly in Florida.

"Looking ahead to summer, we might not be celebrating the demise of this El Niño," cautioned Patzert. "It could be followed by a La Niña, which could bring roughly opposite effects to the world’s weather."

La Niñas are essentially the opposite of El Niño conditions. During a La Niña episode, trade winds are stronger than normal, and the cold water that normally exists along the coast of South America extends to the central equatorial Pacific. La Niña episodes change global weather patterns and are associated with less moisture in the air over cooler ocean waters. This results in less rain along the coasts of North and South America and along the central and eastern equatorial Pacific, and more rain in the far Western Pacific.

El Niño events are part of the long-term, evolving state of global climate, for which measurements of sea surface height are a key indicator.

For an animation of the evolution of the 2015 and 1997 El Niños, click here.

For more information on how NASA studies El Niño, click here.

To learn more about NASA’s satellite altimetry programs, click here.

For more information about NASA’s Earth science activities, click here.

Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Latest from Greenhouse Management

- Jackson & Perkins expands into Canadian market

- Green & Growin’ 26 brings together North Carolina’s green industry for education, connection and growth

- Marion Ag Service announces return of Doug Grott as chief operating officer

- Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden debuting new perennial section at 2026 Breeder Showcase

- The Garden Conservancy hosting Open Days 2026

- Registration open for 2026 Perennial Plant Association National Symposium

- Resource Innovation Institute and North Dakota State University explore co-location of data center and greenhouses

- Fred C. Gloeckner Foundation Research Fund calls for 2026 research proposals